Prediction Markets: Crossing the Chasm (pt. 1)

It's all about the liquidity, stupid.

For prediction markets to grow beyond being just a quadrennial spectacle (and the plaything of nerds) to be a regular fixture in people’s lives and become their go-to authoritative source for most event probabilities, entails moving away from the design of first-generation prediction markets.

First-generation protocols, where liquidity provision is a loss-making gambit (and hence constrains liquidity provision to centralized entities with ulterior motives), is simply inadequate for a future where you want prediction markets to become a staple of people’s information diet — the decentralized source of truth spanning hundreds of concurrent world events.

This article will dissect the concept of prediction markets, discuss the historical evolution of prediction markets, what designs do prediction market protocols tend to converge towards in the past, and the bottleneck in liquidity provision confining the scale of current prediction markets.

A Primer on Prediction Markets

Prediction markets are fundamentally a simple premise: it is a bidirectional trading market for bettors to express a view over an outcome.

The concept borrows from Friedrich Hayes’ assertion, that the price system in a free market accurately expresses the aggregate views of market participants over the traded asset. In the case of prediction markets, assuming a free market environment, the price per share will reflect the aggregate view of market participants over the likelihood of the traded outcome.

Hence, prediction markets form reliable unbiased indicators over the probabilities of an outcome, backed by the skin-in-the-game of profit-motivated entities participating in the market.

Isn’t it just glorified betting?

The main difference between prediction markets and betting platforms lie in the manner of how odds (or probabilities) are derived for an outcome:

In prediction markets, the free market determines the odds of an event, calculated as a byproduct of betting flows on either side of the bidirectional trade.

In betting platforms, the operator or bookie forms an opinionated understanding on an event and sets the odds for bettors to bet on (with a margin of error). Bettors are welcome to bet against this opinion, and if they’re proven correct, then the operator will lose money. The free market has little influence over a bookie’s offered odds — “feedback” is in form of profits (if the bookie’s opinion is in line with the free market) or losses (if “wrong” from actual truth).

Henceforth, prediction markets are treated as a more credible source denoting the ‘true’ odds of an outcome happening. Odds obtained from betting platforms merely represent the opinion of the operator or bookie (although they are incentivized to make them as competitive as possible in order to attract betting volume) — it doesn’t reflect the true probability of an outcome.

The Bettor-Viewer Flywheel

Betting and prediction markets are not mutually exclusive. Betting volumes contribute to the liquidity stock of a well-functioning prediction market, and the more liquidity is involved in a prediction market, the more accurate its odds will be perceived, since there are more people with skin-in-the-game and more monetary resources at-stake in that said prediction market.

An efficient prediction market is the result of two thriving yet distinct user groups feeding off each other: profit-seeking bettors who form the “money base” of the market, and information-curious viewers who form the “attention base” of the market.

Increased attention helps get prediction markets to the eyes of profit-seeking bettors;

Bettors place bets against what they deem to be mispriced odds on a prediction market, contributing to that market’s volume and repricing of odds;

Interested viewers put greater weight on the accuracy of the prediction market due to the increased volumes, increasing attention and attracting more bettors into the mix;

Bettors place increasingly sized bets against the prediction market’s odds as open interest (OI) grows and the market becomes able to take in top-dollar bets;

Volumes boom, and viewers increasingly regard the prediction market as the source of truth for that event, further increasing its popularity which attracts more bettor eyeballs;

ad infinitum.

Prediction Markets, v1

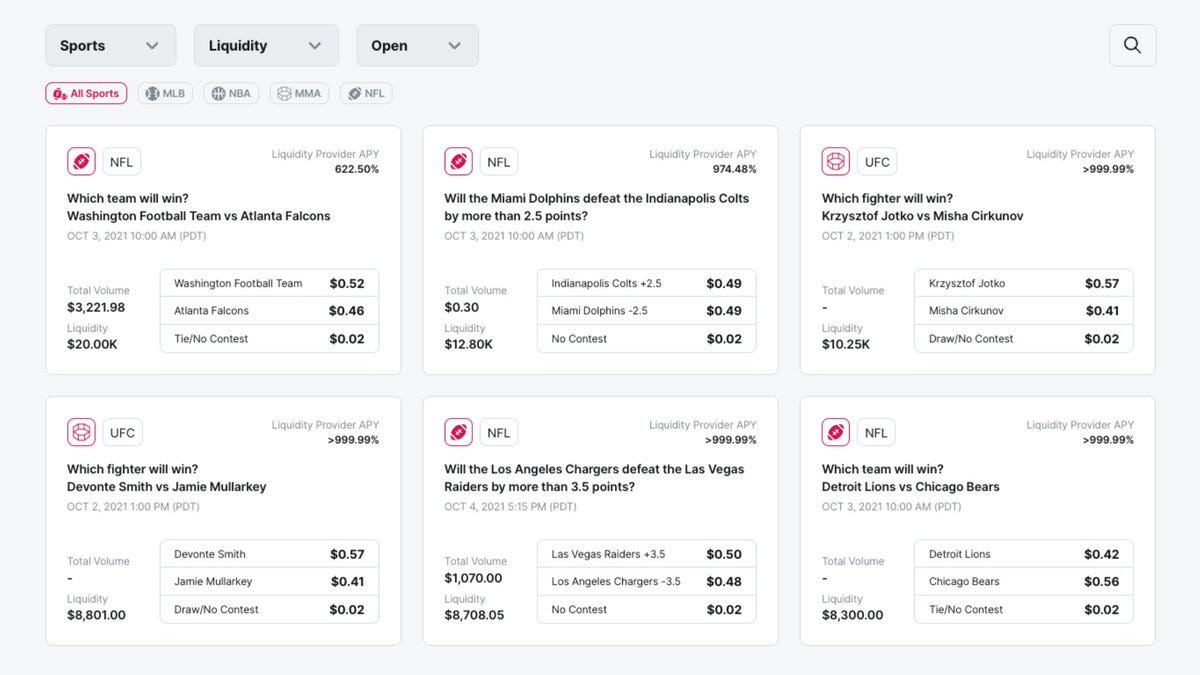

Pioneered by Augur, refined by Gnosis, and later popularized by Polymarket, first-generation prediction markets are implemented either via AMMs or orderbook.

AMM

AMMs became prevalent at a time when blockchains haven’t possessed sufficient scaling capacity to facilitate orderbook-based markets. In the case of prediction markets, each event is represented via a simple 2-pool AMM consisting of two tokens: a YES token, and a NO token.

Initial liquidity is seeded to the AMM by an entity (e.g., market makers) — this forms the market’s redeemable collateral base on event resolution. Participants trade YES and NO tokens against the AMM, which moves prices depending on betting flows. Also, the more liquidity the AMM is seeded with, the less sensitive prices will change per dollar of flow.

Orderbook (CLOB)

Advances made in blockchain scalability (and proving capabilities) results in the renaissance of the onchain CLOB model. In the case of prediction markets, each event has their own orderbook where participants may place bid/ask orders to trade YES and NO tokens.

Market makers are employed to make liquidity for each orderbook-based prediction market, and price movements will depend on betting flows with regards to liquidity: the more liquidity market-makers dedicate to the orderbook, the less sensitive prices will change per dollar of flow.

The Liquidity Bottleneck

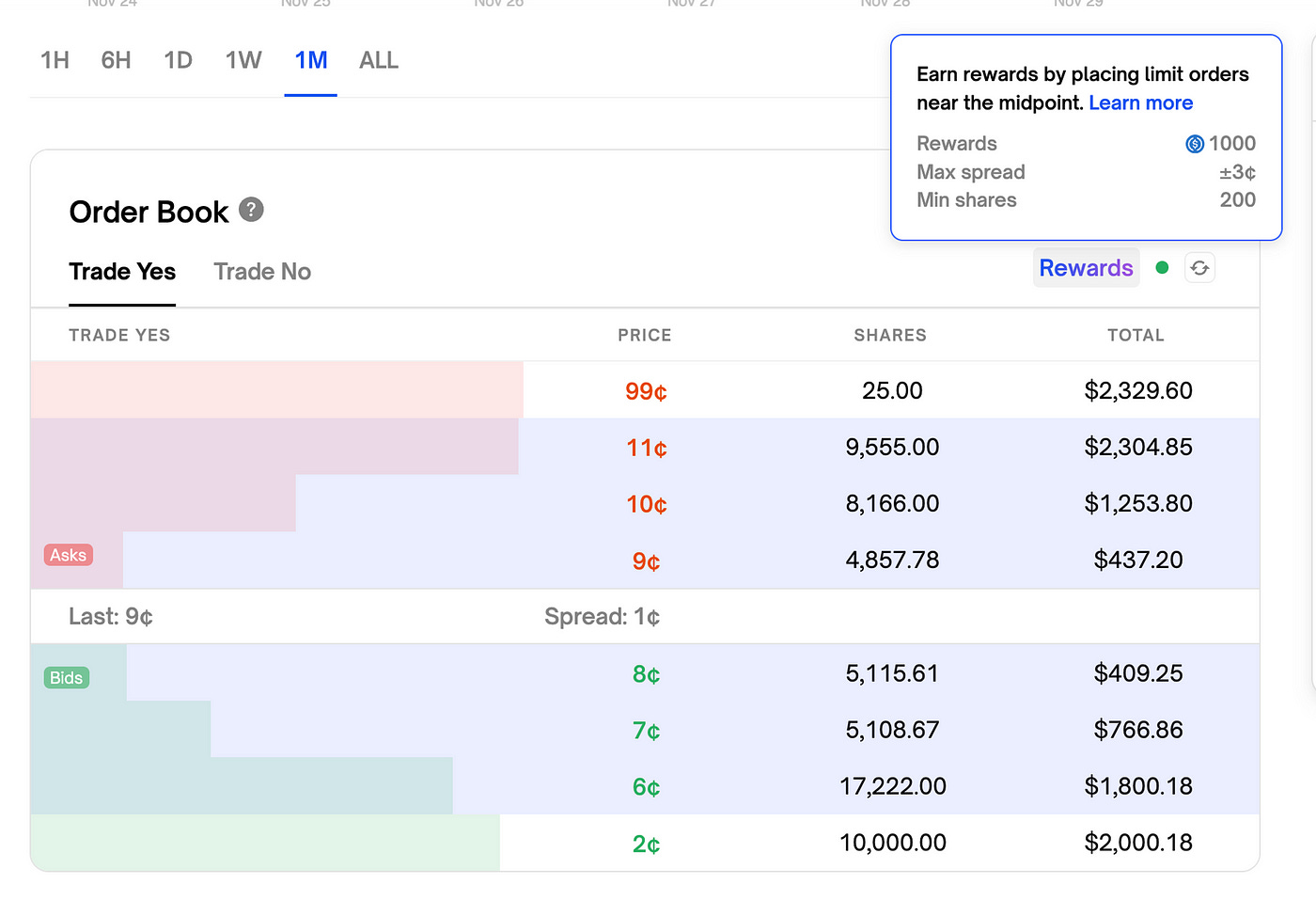

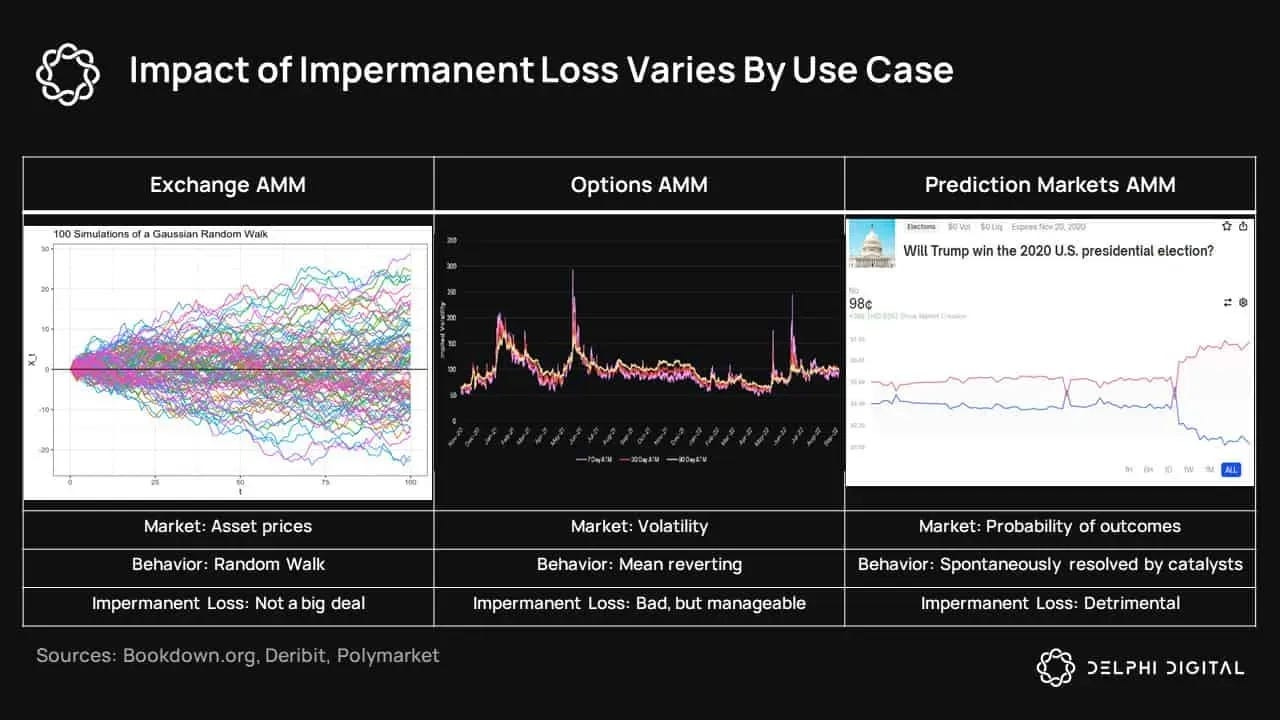

When providing liquidity to a market, you will be exposed to the risk of Impermanent Loss (IL). In the case of AMMs, this will be the price differential between the point when you first deposited liquidity into the pool and the current point to which you want to withdraw your liquidity from the pool. In the case of CLOBs, this will be the difference between the orderbook’s current price and the aggregate prices of your top-of-book liquidity provision (buy/sell orders) for the orderbook.

Market-making in “conventional” markets (e.g., spot markets) is already hard enough: Uniswap LPs often had to be compensated via external rewards outside of fees just to breakeven when providing liquidity for non-correlated asset pairs. This is demonstrated by the makeup of LPs on Uniswap, where the majority of its LPs are in fact made up of highly sophisticated entities (i.e., Wintermute).

First-generation protocols, whether AMM- or CLOB-based, impose unrealistic expectations on LPs to manage their liquidity on individual prediction markets. For prediction markets, where odds swing from 40% to 95% in as short as a few minutes time, liquidity provision is simply a fool’s errand. One injury-time goal, the sudden withdrawal of a political candidate, the revelation of an election’s quick count results, or a knockout win by an MMA fighter — all of these cases will leave LPs on the hook, staring down at the barrel of their now-unrecoverable ILs.

With such high levels of principal risk, nobody is simply bothered enough to provide liquidity for prediction markets — ironically the very lifeblood driving accurate odds in the first place. This constrains the available pool of liquidity only to well-resourced centralized entities who are able to shoulder the principal risk in exchange for under-the-table benefits — definitely not the ideal status quo if you want a truly decentralized yet scalable prediction markets protocol.

Towards Scalable Prediction Markets

The cardinal rule to market efficiency: the more liquidity available for a market, the more it attracts market participants, the more efficient the market gets, and the more accurate its prices will reflect the reality of its underlying asset.

This applies to bond markets, currency markets, stock markets, and especially prediction markets, for which its entire premise lies in its ability to report accurate probabilities for a particular event or outcome.

“Liquidity is by far the biggest issue. When markets are illiquid, they are inefficient, which then calls into question whether they are indeed a source of truth. The more liquid a market is, the more efficient and ‘truthful’ it becomes.” — @mrink0

As prediction markets are increasingly being relied upon by society as an unbiased source of truth for world events, enabling trust-minimized and scalable liquidity provision is of paramount importance.

Unlike most of its industry peers, Azuro does not use the orderbook model as the mechanism underpinning its prediction markets, opting for a dynamic AMM-based approach under a singular concentrated liquidity pool model. It is the only protocol in production today that enables passive algorithmic liquidity provision, where LPs are protected from the risk of Impermanent Loss (IL).

This article is the first part of the “Crossing the Chasm” series on prediction markets.

The second part will be a deep-dive on the architecture of Azuro protocol. Stay tuned!